From Rage to Righteousness: Exile and Redemption in 1930’s Glenville, Ohio

Given the recent rise in open anti-Semitism around the world, I thought it might be a good time to share an old paper I wrote about Superman’s origins which, I think, cannot be separated from the stories of Jews around the world.

Who is Superman? Why was he created? Who was he to his creators? My paper explores the first draft and final product of a hero who was created as a response to fear and uncertainty in a time of anti-Semitism and economic depression.

From Rage to Righteousness: Exile and redemption in 1930's Glenville, Ohio

There was a feeling of powerlessness for Jewish immigrants in 1930s Glenville, Ohio. Although some were successful professionals in their communities, life in diaspora was not easy for them. One place where there was a semi-thriving Jewish presence was in the comic book industry. For us to understand how some Jews may have felt at the time, we will examine a lasting Jewish creation from that period that can give us insight into the North American diaspora experience.

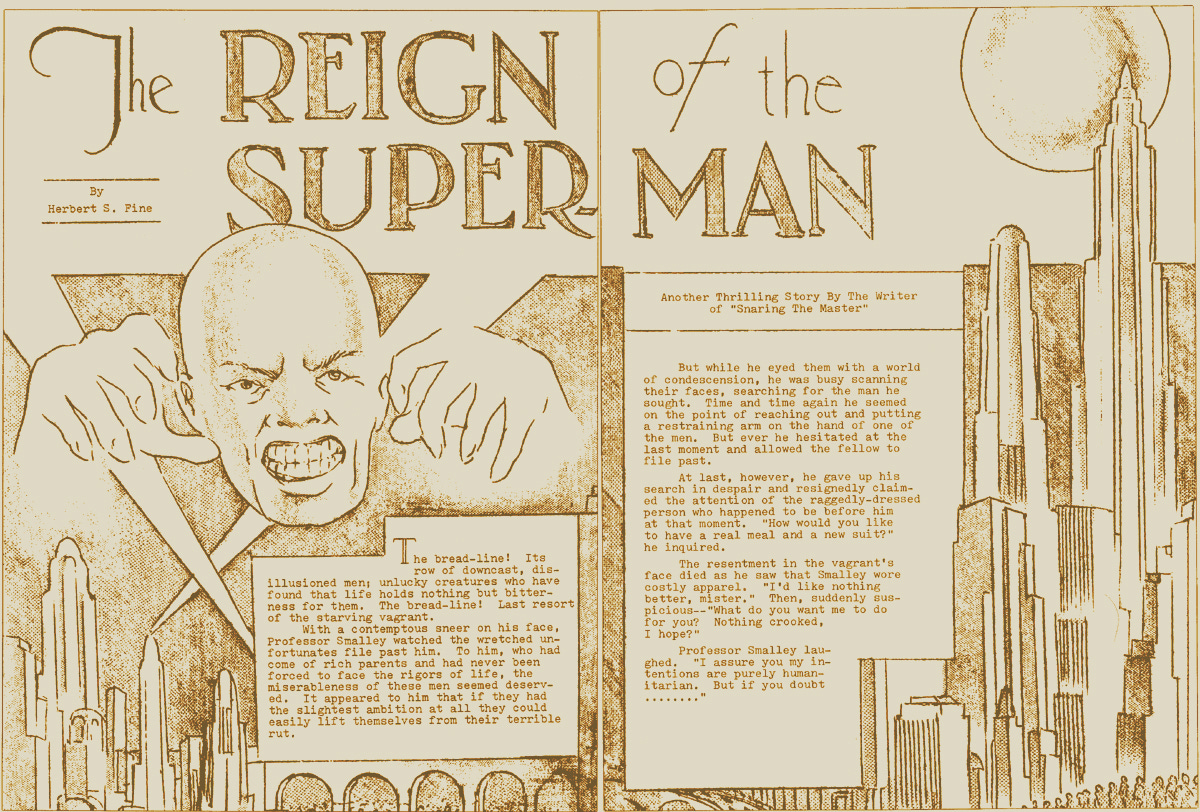

Analyzing comics critically can be a valuable way to gain relevant insight into cultural experiences. We must remember that “comics do not exist in bubbles or vacuums: they are socio-cultural artifacts that must be studied as products - both physical and ideological - within the timeline and cultures they evolve from” (Ricca “History” 190). In analyzing Superman, then, we must not be distracted by the pulp format of the 1930s comic book medium, nor by the pop cultural baggage that has accumulated around the icon from the 1930s to this day. Instead, we must focus on the socio-historical realities and events that influenced its writers to create the comic, to better understand how they were reacting to their life in 1930’s Glenville diaspora. The history and socio-economic realities of Siegel and Shuster, in particular, were marked by their status as new immigrants who did not fit the ideal European type, according to Western immigration standards of the early 20th century, and, that alien status inevitably, as we will see, came to express itself in their artistic productions. I do not claim here that Siegel and Shuster did all this consciously, but rather that writers cannot help but write what they feel. Arthur Miller, when “questioned about whether he intentionally made Willy Loman Jewish, replied that he wasn’t thinking of him that way consciously, but he nonetheless did not dismiss such an interpretation and indeed sanctioned it” (Broad xxv). In the case of the Superman comics, the evidence that Siegel and Shuster were expressing their feelings towards diaspora through their comic book writing is overwhelming. Many people do not know that the character was first named not in Action Comics #1 (1938), but in an earlier, far different, comic strip called “The Reign of the Superman” (1933). So, uniquely, we are fortunate enough to have not one origin story for Superman, but two; and by analyzing the differences between “The Reign of the Superman” and Superman’s later, more famous, origin story, most fully expanded in Superman #1 (1939), we can see how Siegel and Shuster’s ideas of exile evolved in the time between the two versions. They began with a reaction to exile filled with rage, resentment, and self-protection, and ended with one that was optimistic and redemptive and may even serve as a guide, by way of metaphor and symbol, for Jews living in the American Diaspora.

“The Reign of the Superman” (1933), their first attempt at creating a character to embody their wish-fulfillment fantasies regarding how to live in diaspora, depicts a bitter and self-interested man. If the writers who created this character were feeling bitter and self-interested while writing it, they had their reasons. The 1924 US Immigration Act limited immigrants from any one country to 2%, the rationale being to “maintain the racial preponderance of the basic strain on [the American] people and thereby stabilize the ethnic of the population” (Ricca, Superboys 10). The Act refers to these immigrants as “aliens,” a clear statement to the Siegels and their young son that they were considered both outsiders and second-class citizens. To add to this, in 1932, during the robbery of a suit from his store, Siegel’s father died of a massive heart attack. The Jewish community considered this a murder, but the perpetrator was neither caught nor punished, and the “event itself was ignored in the city’s biggest local newspaper” (7), a clear message to the community that the death during a robbery of a local Jewish man was considered inconsequential. Meanwhile, the news of Hitler’s growing popularity, as well as his narrow loss in Germany’s elections, was worrisome, and anti-Semitic rhetoric was on the rise. This must have served as a constant reminder that Jews couldn’t feel safe anywhere on Earth – they had no safe haven, no place to hide - a constant and bitter reminder of their exilic status. Shuster’s father, for his part, lost his job during the Depression, and their family was now barely scraping by. In 1924, the Shusters moved from Toronto, Canada, for the promise of a new land where they could live comfortably through manufacturing in Cleveland (13). Here, in their second North American diaspora, the Depression took its toll. Competition for even menial jobs was fierce, and against the Jews, “blatant employment discrimination existed” (Gartner 302). The boys must have felt the need for a cathartic expression of their anger and hopelessness, of their feelings of resentment for the community that despised them, because they both poured themselves into their separate, but soon to merge, passions - writing (Siegel) and drawing (Shuster). The product of their combined resentment and hopelessness and rage was “The Reign of the Superman.”

Siegel had been writing for the Torch, Glenville High’s student newspaper, since his Freshman year. His dream was to write fantastic stories like the ones he had read in the early science fiction comics, comics primarily written and published by Jews who, due to anti-Semitic quotas, could not break into the regular publishing or advertising industries. Up until this point, he had been unsuccessful in becoming published and so decided to run his own ‘zine called Science Fiction. Shuster and Siegel’s creation, “The Reign of the Superman,” begins with a drawing of a futuristic city, possibly how a suburban teenager from Glenville might perceive the big city of Cleveland, with a long line of downcast people waiting in a bread line that seems to extend to the end of doom. Shuster’s father may very well have once stood in such a line. Siegel fills in the words over Shuster’s image. He tells the story of a vagrant man, Bill Duncan, who, during the Depression, is approached by a well-off scientist who offers him a new suit and a meal. The chemist remarks that, with this change of clothes, the vagrant becomes a different person (Ricca Superboys 70). This desire to become a different person, this self-effacement, is unique to this early version of Superman. Unlike the later Superman, who disguises his true identity but still stays proudly himself, this earlier Superman is happy to leave his original vagrant self behind. This is the ultimate solution to the diaspora problem - to cease to be a Jew. It is not immediately apparent to the vagrant why the scientist is doing this for him, and the vagrant even expresses hope that the man does not expect his kindness to be returned, in the demand for some crooked deed. The vagrant accepting the meal and the suit feels strongly like a metaphor for the Jews accepting the kindness of their new homeland in granting them citizenship. However, this moment in the comic reveals a steep level of distrust for the people who seem to be helping. From this, we may learn that while the Jews of Cleveland had accepted the gift of immigration, it was not without fearing its cost. An “us and them” mentality was still strongly maintained. By accepting the gift of immigration, a debt was incurred, which perhaps led to a deep concern among the Jews, and a questioning of America’s motives and intentions. They came here, but they did not necessarily let down their guard, and in the comic at least, the vagrant is right not to. The scientist’s plan soon becomes clear; using the vagrant as a test subject, the chemist injects him with a serum. The serum gives Duncan special abilities, like mindreading and super-eyesight, along with the power to subject people to his will.

What is significant about all this is that the Superman they first created was no hero. He is just trying to thrive. He is thinking of his own survival. We learn what Siegel and Shuster may have fantasized about in their exile – superhuman abilities to protect them from those trying to destroy them. In order to lead a successful life, they need to take things into their own hands and defeat the oppressive world around them. The vagrant realizes that with these newfound powers he can “live the life of a prince” (Ricca Superboys 71). He announces, “I must remedy my financial situation,” just as Siegel and Shuster must have felt in regard to their ability to support their families. “A grin of superiority then crosses the Superman’s face,” and the character is named. Only a Superman, who takes his own fate into his own hands, could achieve any success in a world so slanted against him. He then absorbs all the knowledge in the universe; in particular, “he goes to the library and reads, ‘Einstein’s book on the expanding universe’ – in German.” This is particularly interesting because Einstein, as a fellow Jew, would no doubt have gained great respect from the young men, and having their vagrant learn Einstein’s theories in German may, it is implied, have given him the power to defeat Hitler. Still, he is no hero. Stuck in his role as a vagrant without hope, he robs a drugstore, though not through violence, instead using his mental powers to convince the owner that he needs the money. We may read this, again, as a reflection of the sort of power Siegel and Shuster, in their hopelessness, fantasized about wielding over the more prosperous gentiles around them. Later in the story, an international council is set up to deal with the Superman problem, and eventually, one member of the board ends up facing Superman just as Superman decides that the world, beyond hope for improvement, must be destroyed. Superman tells the board member, “I am about to send the armies of the world to total annihilation against each other.” Superman has a “twisted face” as he “broadcasts his thoughts of hate which would plunge the Earth into a living hell.” This extreme reaction to diaspora - a scorched earth policy, not unlike God’s treatment of the enemies of the Jews through much of the Hebrew Bible - shows that, at this point, Siegel and Shuster felt no hope for their futures in exile, and they fantasized about revenge. With Hitler’s armies in Europe, the rise of anti- Semitism everywhere, and the lack of opportunities in their diaspora, one could see why Siegel and Shuster felt the way they did. What happens next in the comic is notable. The board member with the Superman, “in his moment of dread and terror, sends up a silent prayer to the Creator of the threatened world. He beseeches the Omnipotent One to blot out this blaspheming devil” (71-72). This is a shocking moment. The blaspheming devil here is Superman, who until now we have been reading as a representation of Siegel and Shuster. It seems as though they immediately felt guilt and self-doubt about the rage and vengeance they were feeling only moments before. They are not even certain, we realize, that their rage-filled reaction to diaspora has been a fair one. The Superman then looks into the future and sees himself once again as a vagrant in a park. This could be read as a symbol of the continuing cycle of exile that the Jews seem destined to repeat. At this point, the Superman’s basic question, and clearly Siegel’s as well, comes into focus: how does a Jew deal with this exile, this life in diaspora? If exile is to be permanent, is there a better way to feel, a better way to react? An epiphany seems to be contained in the next lines: “I see now how wrong I was. If I had worked for the good of humanity, my name would have gone down in history with a blessing - instead of a curse” (72).

Despite everything bad that was happening at the time, there were other ways to look at their North American exile. One more positive way to live life as a Jew in Cleveland was embodied by the local Reform movement. Rabbi Gries commented on the construction of Tifereth Israel: “We have chosen to omit symbols which proclaim the oriental and the foreign. Our temple is none the less Jewish.... Let then the appearance of our temple proclaim to all, that we are not a people in the midst of the nation, that we are not foreigners, nor children of the East, but that we are Americans... and all our hopes and happiness in the occident” (Gartner 155). For Gries, nothing essentially Jewish is lost by removing foreignness from their synagogue. One can become American on the outside and still remain Jewish. This is not the complete abandonment of the old identity we saw in “The Reign of the Superman.” Gries emphasizes that the Jewishness remains intact. Edward M. Baker, a young Jewish financier who was a reform rabbinical student, offered a reason this transition should be simple. He expressed the faith that the basic tenets of “Judaism and the American Spirit” were in harmony (Gartner 153). He adds, “Let, then, a knowledge of Judaism and a consistent practice of its precepts be the Jews’ contribution to American life.” In the views of both Gries and Baker, the Jews are now Americans. The Jews need to act like Americans, which is not a far stretch, since Jews and Americans share the same values. Seemingly unaffected by the negative aspects of being a Jew in North American diaspora, one classmate of Siegel’s romanticized Glenville, emphasizing this possibility for harmony. Charles Redlick gives us an exciting tour of his neighbourhood:

"You should never take a streetcar if you want to travel on 105th street. If you do, you will miss its atmosphere. The best time to take your stroll is between eight and nine o’clock in a Saturday night... [Newsboys] are shouting to let you know that gangland warfare has broken out anew and the body of a notorious gangster has been found shot to death....You lift your chin up...and on your left you see something that makes you slow down. There is a large, long, low, church with beautifully colored pictures in its windowpanes. You find yourself in the midst of the Jewish section of the street. You see old women gathered at street corners...They are prattling away in some foreign tongue you cannot understand. You pass butcher shops with curious Hebrew hieroglyphics on the windows. When you notice a delightful odor in the air, which makes your very blood tingle, you turn around to find that it comes from a store which has the sign “Delicatessen” in it, then you know you are in the “corned beef belt”. Do not walk in to buy if you have just eaten, because you must be hungry to appreciate the delightful aroma and taste of these corned beef sandwiches" (qtd. in Ricca Superboys 20-21).

We can see that Glenville has its problems, gangland warfare for example, but what is most apparent in this description is the blending of two worlds. He recommends that you walk on 105th to enjoy its atmosphere. A long low church he describes as beautiful, and he mentions this immediately before you arrive in the Jewish part of the street where the Hebrew butcher shops co-exist peacefully with the church. Foreign tongues and strange writings are exciting to him, rather than threatening, and everyone, Jew or Christian, despite their differences, can all appreciate a hearty corned-beef sandwich. So, despite the lower status of the Jews in terms of social respectability, Glenville could also be seen as a haven where they felt relatively safe. Ultimately, the positive view shared by Siegel’s high school friend won out, and we can see this in the second attempt at creating the Superman character. If we analyze Superman #1 (1939), we realize that Siegel went even further than the suggestions of Gries and Baker, by creating a character that not only fits in while making a contribution, but also becomes a hero for both his people and others who aims to bring redemption to all.

As an infant, Superman is sent to Earth, in particular North America, by expedient means (Siegel 195). In the comic, it is by way of a rocket, and, in the cases of Siegel’s and Shuster’s parents, it was also in haste, fleeing pogroms. The “alien” or “immigrant” child is “adopted” by his North American parents and named Clark – a nondescript American name signifying an attempt to blend into this society. Clark’s adoptive parents tell him he must hide his great strength from people, or “they’ll be scared of you!” When Clark’s parents pass away, he decides he must turn his “titanic strength into channels that would benefit mankind.” And so was created Superman – “Champion of the Oppressed. Sworn to devote his existence to helping those in need” (196). Unlike the previous Superman, this one wants to blend in while still keeping his core identity. Disguised as a typical American, Superman marches into the office of the Daily Star and asks for a reporting job. He is refused. “Sorry, fella! Can’t use you!” (197) may have been a common reply to Jews at the time who tried to enter the newspaper industry, but Clark does not take no for an answer. To secure a position at the Daily Star, he tries to gain the respect of the editor and prove he can do the job well. “Sounds like my big chance to impress the editor!” Clark exclaims. Clark wanting to impress the people in his adopted homeland shows that, rather than hating these people, he respects them. This is a very different approach to living in an exilic community than the resentful, vengeful one we saw in “The Reign of the Superman.” It is not a new idea in Jewish history to live by the law of the land peacefully by taking on some of its customs and appearing to assimilate. This notion in the comic echoes statements made centuries earlier by Maimonides. In 1162, Maimonides wrote a letter in defense of the Jews in Morocco who had to hide their worship and act as though fully assimilated (Nuland 42). The letter goes on to cite “Talmudic passages confirming that one is permitted to save his own life by disguising himself in times of persecution, and tells of the stratagems leading rabbis used in the past to convince Roman soldiers that they were not Jews” (43). This, in fact, was how Maimonides recommended Jews at the time to survive in Spain. Maimonides was not calling for an abandonment of one’s Jewishness, but was merely suggesting that, to survive, one should, if need be, keep such acts in private. So, in creating Clark Kent, Siegel presents a philosophy about living in diaspora that echoes advice from Maimonides.

Another trait of the new Superman character is his constant pursuit of justice. Modern readers would be surprised to see the original villains that Superman fought. These were not supervillains; they were regular people doing common crimes. In these quests for justice, he combats domestic abuse, gangsters, crooked politicians, and business owners who care nothing for the safety of their workers. This notion of maintaining social justice even during exile was also a tenet of Maimonides, who had strong convictions when it came to doing good, and insisted that “tzedakah must be a motivating force in the life of every Jew, not only in the form of monetary charity, but as social justice, benevolent deeds, and ordinary kindness” (Nuland 113). Superman, then, even in his exile, employs this tenet of tzedakah as a motivating force. Most fascinatingly, in many cases, Superman, in dealing with criminals, rather than simply throwing them in prison, teaches them lessons, and makes them see the error of their ways, thereby aiding both the victims and the criminals. So, punishment is not particularly a goal for Superman so much as guidance. On top of all this, all those he helps are not his own kind. This too, evokes Maimonides’ philosophy, which makes it clear that those who need to be cared for are “not only Jews, but all people” (Nuland 112). Ultimately, this second version of Superman has decided that appearing to assimilate, doing good deeds, pursuing justice, and helping others (both good and bad) is how he is going to make the best of his diaspora, and maybe even, as we will see, achieve redemption.

We know that, before writing Superman, Siegel had in his possession a book called The Great Book of Magical Art, and that, in this book, he found the inspiration for Superman’s family name – El (Ricca Superboys 105). El, in this book, is said to represent the Hasmalim (angels, according to Jewish mysticism) who bestow clemency and justice on all (De Laurence 225). The chapter of the book with El is on Kabbalistic magic. It is said in Kabbalah that mitzvot (or good deeds) are used to repair the universe (Segal 172). According to Isaac Luria’s Kabbalah doctrines, “the primordial shattering of the vessels of Shekhinah left us with a world in which sparks of holiness and husks of evil (kelippot) are strewn together in confusion... In such a world, the ultimate goal to be pursued by humans consists of liberating the holy sparks from among the husks and elevating them to their proper level of sanctity.” Knowing that Superman is named after an angel of righteousness, and that the text that inspired Siegel was Kabbalah, we get a better picture of how Siegel and Shuster finally saw their redemptive roles in their North American diaspora. Their character Superman seems to be an angel, repairing the shards of glass of the universe by doing good deeds and by guiding others. He is not just an angel for his own people, but an angel for everyone. Superman, then, can be read as a guide for Jews on how to not only live in exile, but also bring redemption for Jews by helping the rest of the world. As the Encyclopedia Judaica offers, redemption is “salvation from the states or circumstances that destroy the value of human existence or human existence itself.” Exile in itself is enough to destroy the quality of human existence, but the character Siegel and Shuster created metaphorically in their likeness makes exile his opportunity to repair the broken world, and that is his redemption.

Superman, the second time around, may have found his redemption, but for Siegel and Shuster, and other Jews, throwing on a cape and pursuing justice was clearly not an option. Writing Superman was a cathartic and symbolic expression of their new positive outlook on their diaspora, but was there some way to make use of those realizations in their own world, the one outside the comic strips? It is important to note that the “comics industry sprung from mostly Jews who were one step away from the immigrant experience and two steps away from social respectability” (Brod 2). The comic book industry was largely run by Jews who were unable to get jobs in other, more respectable, types of publishing. This rugged form of publishing was considered “shmate. . .a junky, throwaway publication,” but behind the comics that Liebowitz and Donnenfeld published existed not only escapism, but also a dialogue between the publishers and the readers. They created a community, and a forum that was embraced by a large percentage of Jews. When a reader wrote into a comic, his name and address was published along with his comments. Readers were therefore encouraged to interact with one another outside of the comics and were able, through their letters, to directly influence what comics kept getting printed and which did not. This dialogical text containing commentaries on commentaries seems almost Talmudic in a sense, and therefore clearly signifies the presence of an underground Jewish publishing world. And, in the same way that Superman was able to help gentiles and the rest of the world from his position in exile, Siegel and Shuster found a way, by creating the Superman myth, to bring inspiration, hope, and guidance to millions of people over the last century; and their creation, shaped by the hardships of the Depression and exile, will no doubt continue to inspire outsiders from all walks of life for years to come.

Works Cited

Abrams, Sylvia Bernice Fleck. Searching for a Policy: Attitudes and Policies of Non-Governmental Agencies Toward the Adjustment of Jewish Immigrants of the Holocaust Era, 1933-1953, as Reflected in Cleveland, Ohio. Diss. Case Western Reserve University, 1988. Ann Arbor: UMI, 1987. Print.

Brod, Harry. Superman is Jewish? How Comic Book Superheroes Came to Serve Truth,

Justice, and the Jewish-American Way. New York: Free Press, 2012. Print.

De Laurence, L. W. The Great Book of Magical Art, Hindu Magic and East Indian

Occultism, now combined with The Book of Secret Hindu, Ceremonial, and Talismanic Magic. Chicago: De Laurence Co., 1915. Print.

Fingeroth, Danny. Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics, and the Creation of the

Superhero. New York: Continuum, 2007. Print.

Gartner, Lloyd P. History of the Jews of Cleveland. Cleveland: Western Reserve

Historical Society, 1978. Print.

Grunblatt, Joseph. Exile and Redemption: Meditations on Jewish History. Hoboken, NJ:

KTAV Publishing, 1988. Print.

Jenkins, Henry. Introduction. Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods. Ed.

by Matthew J. Smith and Randy Duncan. New York: Routledge, 2012. 1-14. Print.

Nuland, Sherwin B. Maimonides. New York: Random House, 2005. Print.

“Redemption.” Encyclopaedia Judaica. 2nd Edition. 2007. Print.

Ricca, Brad. “History: Discovering the Story of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.” Critical

Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods. Ed. by Matthew J. Smith and Randy Duncan. New York: Routledge, 2012. 189-200. Print.

---. Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, The

Creators of Superman. New York: St.-Martins, 2013. Print.

Rubenstein, Judah and Jane A. Avner. Merging Traditions: Jewish Life in Cleveland.

Kent: Kent State UP, 2004. Print.

Segal, Eliezer. Introducing Judaism. New York: Routledge, 2009. Print.

Siegel, Jerry and Joe Shuster. The Superman Chronicles. Volume One. New York: DC

Comics, 2007. Print.

T.L Newman © 2013