Getting the press to explore the proposed dental benefit is like pulling teeth.

Spoiler Alert: The benefit is not Following the Science

This piece is not about MGTOW or a prosthetically-enhanced woodworking teacher or any other culture war issue. For my first article on this site, I have purposely chosen a mundane topic - dental care - to show that even when it comes to reporting on issues that are not culturally loaded, the press in Canada is dragging its feet.

Hopefully, this piece will provide Canadians with the necessary information to understand current dental care coverage and services for children across Canada, its challenges, and who experts say are the Canadians not visiting the dentist. It also aims to capture a bit of Canada’s overall state of oral health.

Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government has entered into a Supply and Confidence Agreement. This means that Jagmeet Singh has agreed to prop up Justin Trudeau and the Liberal party, effectively shielding them from a no-confidence vote and the triggering of an election. In exchange, Singh has made many demands, one of which is for the federal government to completely take over provincial dental care for Canadians. This demand, which was announced with great fanfare, has since devolved somewhat into an agreement for an additional income-proved credit that meshes with existing provincial and territorial child dental coverage.

Here are the details of that coverage, according to the government website. Children in families with household incomes of $90,000 or less will be able to apply for a government benefit “if they do not have access to a private dental care plan” and with the condition of “no co-pays for anyone under $70,000 annually in income.” It then goes on to seemingly contradict itself by saying, “Children already covered under another plan may also be eligible if not all dental care costs are paid by the program.” As with all government credits, applicants must have filed their 2021 taxes, be qualified for and receive the Child Tax Benefit (CTB), have a MyCRA account, and have set up direct deposit. If Royal Assent is received, Canadians will be able to apply for the benefit after December 1st, 2022.

The government website does not elaborate further. However, a recent article in the Globe and Mail does break down the “plan,” now more aptly called a “benefit.” It provides the additional information that “families with no existing dental coverage and income less than $70,000 will be eligible for cheques of $650 a child annually. The amount drops to $390 if the family income is between $70,000 and $80,000 and to $260 for families with income between $80,000 and $90,000. Families with income above $90,000 will not be eligible for the program.”

On May 5th, The Globe and Mail reported that the NDP’s Andrea Horvath, if elected, would be putting forward an Ontario Dental Plan, something at least as ambitious-sounding as Jagmeet’s heretofore-Plan-now-Benefit. She told Ontarians her new proposed provincial dental plan would “save a family of four $1,240 a year on basic check-ups and filling a cavity, and if both kids need braces, the plan could save them more than $13,000.” She assured Canadians that “the plan would be in place before promised federal dental coverage is fully developed, and once the national program [was] up and running, the provincial plan would ‘mesh’ with it.” A provincial plan that covered orthodontics must have seemed too rich for Ontario taxpayers, or at least it wasn’t on the top of their priority lists, because Horvath lost that election to a Progressive Conservative who easily won a second majority. Still, Jagmeet’s ambitions were not curtailed.

Nonetheless, some experts are worried about the design of the federal plan. According to Carlos Quiñonez, Vice-Dean and Director of Dentistry at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University, “The government will need to carefully work out how to deliver dental care to uninsured people without disturbing what is ostensibly a relatively good system.”

It has also been suggested by Lindsay Tedds, an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Calgary, that this new “plan” or “benefit” will expose Canadian families who do not use the credit for dental services to clawbacks, due to the way it is designed, which is similar to the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, which many Canadians are now paying back thousands of dollars for because they received more than they were qualified for.

Tedds believes these clawbacks are going to happen. “They’re setting it up to happen,” she said. Tedds pointed out that “many low-income families already qualify for provincial dental coverage and may not use all the money they get from the federal government. Others may lose their receipts or use the money for other pressing needs.” The way Tedds sees it, “Unless the government changes the criteria, some marginalized families are going to face consequences from the Canadian Revenue Agency.”

But wait a minute - aren’t we already getting ahead of ourselves here? Shouldn’t we take the time to look at what currently exists in each province and territory for children’s dental coverage? Otherwise, aren’t we starting off by assuming, without evidence, that all provinces and territories have problems with their existing dental plans for children up to age 12, and, that it is the federal government's job to swoop in and offer benefits to cover insufficient provincial plans with Canadians’ federal tax dollars?

I will leave it to my readers to ultimately decide whether it is acceptable to force Canadians living in provinces with functional dental care programs for children to pay higher federal taxes to compensate for provinces that do not if, in fact, we find out that is happening.

My guess is, though, that if Ontario residents desperately wanted greater dental coverage, and their provincial taxes raised to pay for it, Andrea Horvath would have been elected. This is one of the reasons the Trudeau-Singh Supply and Confidence agreement is troublesome. It allows an existing leader like Trudeau, and an unpopular one at that, to maintain power by accepting an alliance with the leader of another party and together offering a benefit that is supposed to be determined democratically by Canadians voting at provincial and territorial levels. In other words, an unpopular federal leader is maintaining power by promising to make certain Canadians pay for things they haven’t asked for, may not need, and almost definitely should be deciding on a provincial level.

Existing Provincial and Territories Dental Plans for Children

Here is what already exists for children’s dental coverage in Canada’s provinces and territories. Those uninterested in reading the details for each province can skip ahead to the paragraph that summarizes the main points below. However, I recommend a quick read-through of this section.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador’s “Children’s Dental Health Program” entitles all children 12 years and under to examinations at 6-month intervals, cleanings at 12-month intervals, fluoride applications for children aged 6 to 12 at 12-month intervals, routine fillings, extractions, and sealants. Parents are advised to check with their dentist if any additional dental treatment their child needs is covered by the program. These services are administered to children through their dentists. No income verification is required.

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia’s “Children’s Oral Health Program” covers all children aged 14 years and younger for 1 routine dental exam, 2 routine x-rays, and 1 preventive service (brushing, flossing instruction, cleaning), fillings, necessary extractions, nutritional counseling, and sometimes fluoride treatments yearly. Residents must use their private insurance first when applicable before the program will provide coverage. These services are administered to children through their dentists.

So far, we see that coverage is similar when we compare Newfoundland and Labrador to Nova Scotia, give or take an extra yearly examination in Newfoundland and Labrador. However, children in Nova Scotia are covered at 14 and younger while Newfoundland and Labrador children are covered as long as they are 12 and under.

Prince Edward Island

In Prince Edward Island, things work a bit differently than in Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia. In P.E.I., the Children’s Oral Health Programs provide all children aged 3-17 with free “Preventative Services,” such as assessment of their risk of developing an oral disease (not a check-up), oral health education, topical fluoride treatment, dental sealants, and teeth cleaning.

As for “Treatment Services,” which are performed in Public Health Clinics or private dentist’s offices, children from 3-17 without private dental insurance must pay 20% of the cost of the following services: annual dental check-ups, x-rays, as well as restorative dental services, fillings, root canal treatment on front teeth, and extraction, unless the family’s net income is less than $30,000 per year, in which case an exemption must be applied for. Children who are referred to a hospital for dental surgery and who do not have private insurance are covered.

So, Prince Edward Island’s 3-17 age range appears generous until you realize the services are tiered. The requirement of paying 20% for dental services rendered to children unless household income is verified under $30,000 also stands out in comparison to the first two provinces. It is also unclear why the province has chosen a school-based entry point to the tiered program in contrast to the previous two provinces and whether this has improved dental health for children aged 3-17 on the island, but it brings up a number of questions. Is this system more effective in terms of achieving better oral health outcomes for children than just having them visit dental clinics like they do in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia? Is it more cost-effective for the province? Do the provinces and territories even collect this data? If so, do provinces and territories share this data and best practices with each other? Wouldn’t it be a good idea for health ministers from provinces to share oral health data and best practices annually, if they don’t already?

New Brunswick

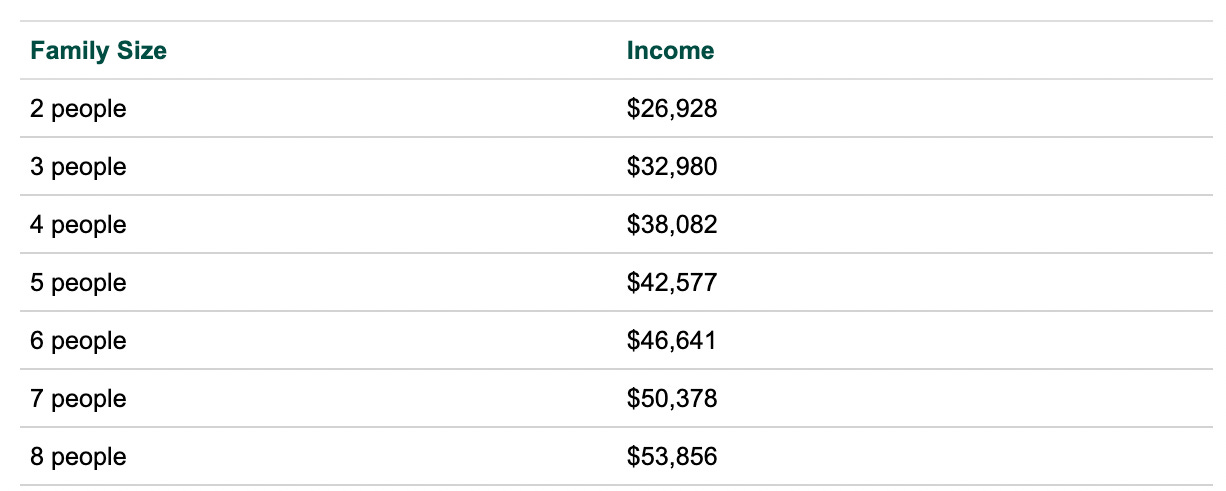

New Brunswick’s “Healthy Smiles, Clear Vision” program covers children 18 years of age and younger if they meet the following criteria: they cannot have coverage through another government program or private insurance plan, and they cannot have a net income level exceeding a specific amount based on the size of the family and the previous income tax return.

Here is the breakdown:

What is included for children who qualify? The plan covers basic items including regular exams, x-rays, and extractions, with some focus on preventative treatments such as sealants and fluoride treatments. Cleanings do not appear to be covered.

So, here we see a second province using an income-tested qualification for children’s dental coverage, but instead of a standard amount of under $30,000, as we saw for P.E.I., New Brunswick’s income-tested qualification uses the number of people in a household to qualify children for coverage. Interestingly, New Brunswick’s plan is quite generous compared to the previous provinces, in that it covers qualified children up to 18 years of age. However, it does not appear to include cleanings. A major drawback of this plan for residents may be that those with an existing dental plan and who do not meet the low-income threshold do not appear to be able to use their private dental plan first and have New Brunswick cover the rest. I imagine this is a sore point with residents there.

In Quebec, RAMQ entitles all children under the age of 10 to receive the following dental services free: annual examination and emergency examination, x-rays, local or general anesthesia, grey amalgam fillings on the premolar and molar teeth, fillings using esthetic materials in certain cases, tooth and root extractions, endodontics, including root canal treatment, apexification, pulpotomy, pulpectomy, the emergency opening of the pulp chamber and sedative dressings, prefabricated crowns, and oral surgery services. Children visit a dentist to receive service.

Some might be surprised to learn that Quebec, which is often considered the most socially progressive province in Canada, only covers children under 10 and does not cover basic services such as cleanings and fluoride applications. There does appear to be some last-resort financial assistance available for those experiencing hardship, with approval determined by Quebec’s MTESS.

Ontario

Ontario’s “Healthy Smiles Program” allows children 17 years old and under to access dental services if they are from low-income households. Some children are automatically enrolled if they receive temporary care assistance, assistance for children with disabilities, and if they or their family receives Ontario Works or Ontario Disability Support. Otherwise, children will have to meet certain household income levels by the number of persons in the family.

Coverage includes regular visits and covers the costs of check-ups, cleanings, fillings (for a cavity), x-rays, scaling, tooth extraction, and urgent or emergency dental care.

The household income verification requirement for Ontario families is calculated by determining the number of dependent children in the household. The threshold to qualify as low-income is noticeably more stringent for those with up to 3 dependent children in Ontario than it is for a family in P.E.I., which requires a household of any size to make less than $30,000 to qualify. While coverage for qualified children up to 17 is more generous, and the basic services are what most would consider reasonable, when comparing Ontario’s income testing to New Brunswick’s, which is by the number of people in the household and not the number of dependent children, Ontario’s is again more stringent. A single mother with one child in New Brunswick has to make under $26,928 to be covered, while the same single mother in Ontario would have to make less than $24,930 to qualify.

Manitoba’s “Smile Plus Children’s Dental Program” provides dental services for children enrolled in several elementary schools in the Winnipeg region, so up until grade 6. For most children, this would likely mean they are covered until they turn 12.

The page for this program says that “The services to be delivered are chosen based on evidence of achieving optimal oral health outcomes” and that the Winnipeg Regional Health and the University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Dentistry “partnered to compile a team of dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants to work with senior dentistry students from the Faculties of Dentistry & the School of Dental Hygiene” to deliver the following services: oral health needs assessments, school and community based oral health promotion, dental pit and fissure sealant treatment, topical fluoride treatment, assertive follow-up for children in need of treatment, and school-based clinical treatment.

This is very different than what we have seen so far in the previous provinces. Eligibility is based entirely on grade level and does not appear to cover cleanings, annual check-ups, or x-rays. Or, if it does, it hasn’t stated it outright.

The free services mentioned are provided solely in schools by dentists or dental students in training. There is no income verification requirement, but there also doesn’t seem to be an option for families to have their children see a dentist in a clinic for free. As a result, Manitoba appears completely reliant on schools and parents with private coverage for the administration of oral health in children under 12.

The Saskatchewan “Oral Health Program” advises parents to call or email their oral health program if they answer yes to the following questions: they have a child under 18 who needs dental treatment and has no or only limited coverage, or if it is a hardship to pay for coverage. No other information is provided as to what will or will not be covered, income verification thresholds, or where the services will be administered if they are granted by the province. Their website states that the “goal of the Population and Public Health Clinics is to improve the oral health of children and youth. These are children with high levels of dental disease, who are referred to our dental public health clinics for treatment” and “the dental clinic team provides basic preventive and treatment services to children up to age 18, who have limited or no dental coverage. These services are provided at no charge when provided by the dental clinic team. The dental team consists of a dental therapist, a dental assistant, and a dentist. Any child who lives in the Saskatoon Health Authority, who requires dental treatment and has the inability to pay for services, can be referred to the dental clinics.”

So far, Saskatchewan provides the least amount of stated basic coverage for children (none) and is incredibly vague about what they will cover and how low-income families might qualify.

The Alberta Child Health Benefit covers health benefits for children in low-income households up to 18 or 19 if still living at home and attending high school. If a family already has health coverage through another plan, the site advises that their existing coverage plan must be used first, and then this plan would be used towards the remaining costs. What is covered? Basic and preventative services like fillings, x-rays, examinations, and teeth cleaning.

This coverage is income-verified and differs again from methods used in Ontario, New Brunswick, and P.E.I. A child in a single-parent family in Alberta will qualify if the parent makes less than $26,023 in comparison to P.E.I. where the same single-parent family would need to make less than $30,000, New Brunswick where they would need to make less than $26,928, and Ontario where the single parent would need to make less than $24,930 to qualify.

British Columbia’s “BC Healthy Kids Program” covers low-income children up until and including the month they turn 19. Families must be approved for coverage and have an adjusted annual net income of $42,000 or less to be eligible. Families have to apply, file their taxes yearly, and update their family accounts if there are changes to their household. Family income for the coverage will be verified yearly. To access coverage, the care card will need to be shown to a clinic and confirm their coverage before each appointment. What is covered? Children are eligible for up to $2,000 of dental services every 2 years. This includes services such as exams, x-rays, fillings, cleanings, and extractions. The brochure says the dentists can advise if other services can be covered. Emergency services for the relief of pain will also be provided if the child’s 2-year limit has been reached.

British Columbia has the most robust income-tested provincial program covering children up until 19. It includes all the basic services one would expect for children and has the least stringent qualifying threshold ($42,000) when compared to the previous provinces. If you have to be income-tested for coverage for your child, you are most likely to be approved in British Columbia.

The Yukon Children’s Dental Program is a school-based public dental health program that provides diagnostic preventative and restorative dental services to Yukon children. It does this through dental therapists who provide dental services to both urban and rural communities. Home-school children and students from Kindergarten to Grade 8 are eligible for services from the Yukon Children’s Dental program in Whitehorse and rural communities with a resident dentist. Home-school children and students from Kindergarten to Grade 12 are eligible for services from the Yukon Children’s Dental Program in communities without a resident dentist. Dental services provided by Yukon Children’s Dental Program are supplied at no cost to the parent or guardian. They are covered by Yukon Health and Social Services. What is covered? Dental examinations, diagnostic x-ray films (if required), oral hygiene instruction, cleaning and/or scaling of teeth, fluoride application, and sealants.

The initial dental examination is performed by a dentist who will also complete a recall examination every two years. In alternate years, the examination will be conducted by a dental therapist.

If your child requires dental treatment following the dental examination, consent for treatment will be sent home to inform parents of their child’s dental needs and to obtain parental written consent. Treatment cannot be provided without written consent from the parent/guardian. Once this has been provided, children then receive the dental treatment prescribed, which may include: fillings (silver amalgam or white composite resins), stainless steel crowns (baby teeth), pulpotomies (baby teeth), extractions if required, emergency dental services, and parent/guardian meetings with the dental therapist to discuss the parent’s concerns about their child’s dental health.

At first glance, this sounds great. Children are covered up to and including grade 12 and all the basic services we would expect children to need are provided at no cost and without income verification through schools.

However, this program was in the news as recently as 2019 because they had to scale back their program due to a shortage of dental therapists that administered the program across the country. Due to the closure of a school that trained these therapists, and the dental therapists moving on and becoming dentists, this robust on-paper coverage has been reduced to basic services such as fluoride treatment or simple fillings by dentists if they can be found. This goes to show that having robust coverage without cost is only part of the picture.

In the Northwest Territories, local healthcare centers work with dental clinics to provide visiting dental services to communities. All NWT residents living in communities that do not have private dental clinics can access visiting services.

The services offered include examinations and x-rays (diagnostic services), cleanings (preventive services), fillings (restorative services), root canals (endodontic services), deep cleaning and gum treatments (periodontal services), removable dentures (prosthodontic services), and basic oral surgery such as removal of teeth (unless extremely complicated). The dentists at these visiting clinics are also able to refer patients to other dental professionals if they require a service that they are not able to provide at the visiting clinic.

Who is covered? All First Nation and Inuit residents are covered by the Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) Program. There is no age limit. All other residents will need to pay for the service through their private insurance plans or extended benefits.

Nunavut

The Nunavut Oral Health Program provides prevention and treatment for children in grades 7 and under. Program services are provided by dentists, dental therapists, dental hygienists, territorial community oral health coordinators, and community oral health coordinators. These services are provided at dental clinics at health centers, schools, daycares centers, community centers, and community health fairs. Incentives and prizes are given to children who keep their appointments. Children who are enrolled in this program are eligible for free dental screenings. Following the initial screening, sealants, temporary fillings, extractions, fluoride varnish, and referral for additional treatments are made available. It is unclear if this includes cleanings, but they are not mentioned outright.

Nunavut’s children’s dental services have appeared in the news quite frequently as being inadequate - not because of the coverage which is free, but because there is a shortage of specialists to administer them. Due to Covid, the already long waitlist of 550 kids waiting for dental surgery almost doubled to 1000. Roughly 90% of children and young adults in Nunavut need dental work, said the chief dental health officer in 2018.

Nunavut’s challenges around dental care for children have nothing to do with coverage and everything to do with education about oral health and the ability to provide timely services. No additional government plan or credit will decrease their waitlist. However, it is possible that a different targeted federal government initiative might help solve the lack of dentists.

Here’s that summary I mentioned

Currently, children’s dental coverage in each province or territory varies by age or grade level, where and how the services are administered (private clinics, schools, community visits), whether or not income verification is necessary to qualify, which services are covered (although most cover what we would consider basics services), whether or not they can be combined with existing private or government insurance, and the availability of services to be administered. It is nice to have free dental services for low-income children or children under a specific age, but I think we can agree that having it free is useless if there are no specialists to provide these services.

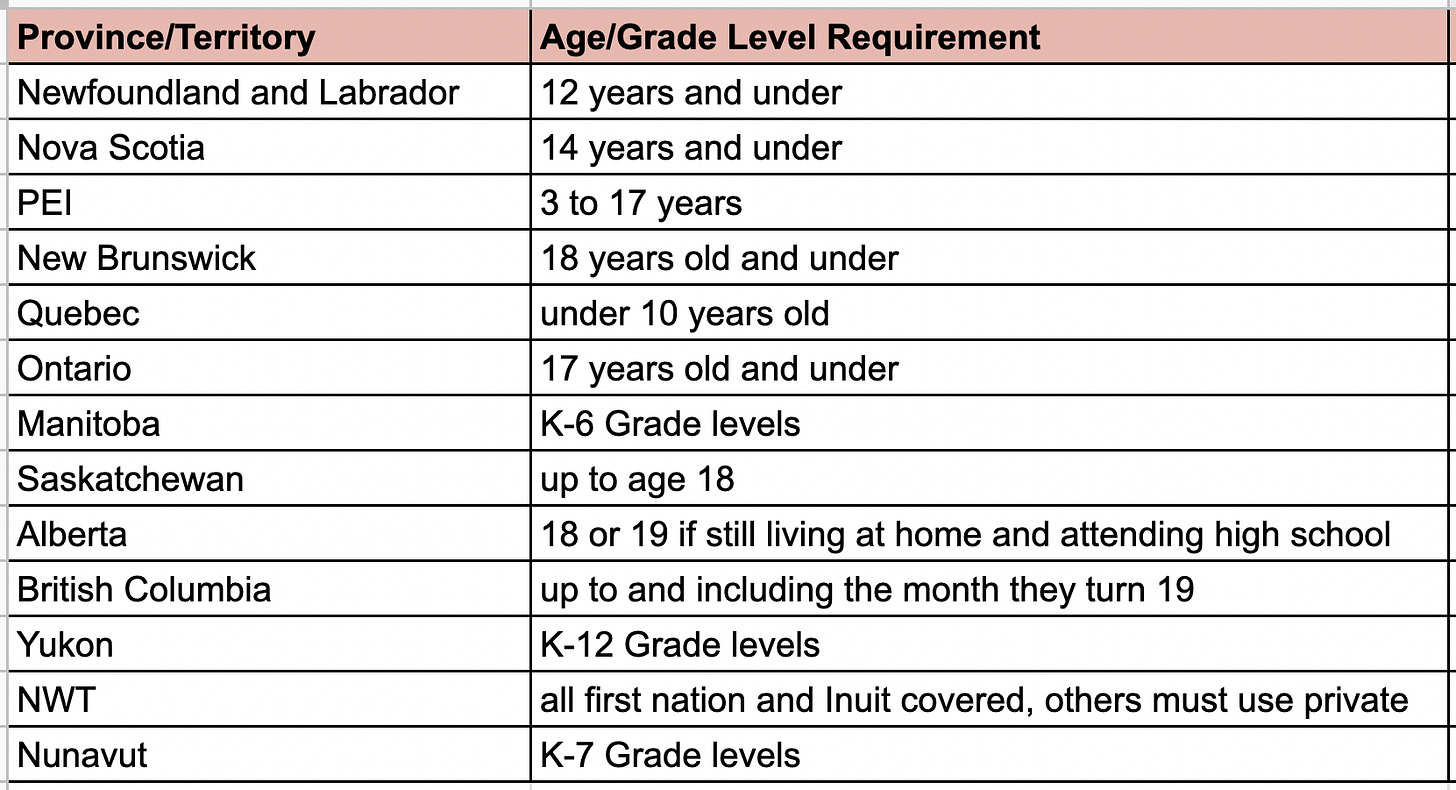

In terms of age or grade level qualification, here is where the provinces and territories stand.

Basic coverage

Most provinces and territories provide a basic level of coverage for children who qualify. I define basic here as annual or bi-annual check-ups, cleanings, fillings, extractions, fluoride treatment, x-rays, etc. The exception to these is Saskatchewan, which does not list any basic services for children as covered and asks the resident to contact them if they are experiencing hardship, Quebec, which surprisingly does not cover cleanings, New Brunswick, and Manitoba. It is unclear whether cleanings are covered in Nunavut, as it is not stated outright.

Qualifying for Children’s Coverage

In regards to having to qualify for children’s coverage, none of the territories require income verification. Five of the provinces, including New Brunswick, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia require income verification in order to qualify for children’s coverage. Each of these provinces uses a different system to calculate whether or not a household is considered low-income. P.E.I. and British Columbia use a set household amount regardless of family size, $30,000 and $42,000 respectively. New Brunswick calculates low income based on family size, Ontario uses numbers of dependants, Saskatchewan tells residents to email or call if they are experiencing hardship but gives no threshold or promise for any coverage for children, and Alberta uses an “adult plus number of children” or “couple plus the number of children” system to assess household income for children’s dental coverage.

The Stringency of Thresholds for a Single-Parent One-Child Family in Provinces that Require Income Verification

In British Columbia, families must have an adjusted annual net income of $42,000 or less to be eligible. This makes it the least stringent in regards to qualifying as low-income. In P.E.I., the same single-parent family would need to make less than $30,000, in New Brunswick less than $26,928, in Alberta less than $26,023, while in Ontario, a single parent would need to make less than $24,930 to qualify. Ontario has the most stringent threshold to qualify as low-income for children’s coverage. (See charts above under these provinces for more details about thresholds).

Ability to Qualify & Combine Private Insurance with Provincial Children’s Coverage

Newfoundland and Labrador provide universal services to all children. There is no mention of having to use private dental coverage first. Nova Scotia also provides universal basic coverage to all children but stipulates that private dental should be used first and then the provincial dental should be used to cover the remaining amount. P.E.I. makes it clear families who have private dental coverage will be covered for some preventative services that take place in schools, but they will not be covered for preventative services that take place in clinics. There appears to be no option for families in P.E.I. to combine private insurance with provincial. Alberta states that residents must use private insurance first but can combine it with provincial coverage. Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia can combine their private insurance with provincial coverage for children. Saskatchewan is purely hardship-based and likely would not allow the combination of private insurance with whatever assistance they might provide. At best, it is unclear. In NWT, all First Nations and Inuit are covered, and all other residents must use private insurance. The Yukon and Nunavut do not mention needing to use private insurance first, nor do they have any restrictions against using private insurance while being covered by the province.

Now that we have a sense of what is covered for children’s dental care throughout Canada, let us take a look at what experts say about Canada’s state of oral health overall and for children, and where our challenges lie.

The State of Oral Health in Canada

According to “The State of Oral Health,” a 2010 report based on the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS), Canadians have very good levels of oral health. Highlights from the report showed that roughly 80% of Canadians in 2010 had a dentist (far more than had a family doctor.). Approximately 85.7% visit a dentist within a 2-year period. The report notes this as a significant improvement in comparison with the early 1970s when it states that barely half of the population consulted a dentist on an annual basis. 84% rate their oral health as good or excellent.

At the time, 32% of Canadians at the time had no dental insurance. 53% of adults between 60-79 had no dental insurance, and 50% of Canadians in the lower income bracket had no dental insurance. 5.5% of Canadians had untreated coronal cavities.

The report shares a chart displaying the percentage of Canadians aged 12 and over that consulted with a dentist or orthodontist in Canada in 2012. Unfortunately, because 12 and under were left out, we cannot use it to judge whether or not the federal government’s proposed plan would have improved dental visits for children.

The study says children from 0-6 are not considered in surveillance studies, and this particular study does not cover children under 12. This is too bad, because if we found out that children aged 0 to 11 are doing just as well for their age range as those aged 12 to 20 (about 78%), keeping in mind the expected amount of visits for children that young, it would help us understand if this new government measure would actually help more children end up at doctor’s offices at the age they should.

While we do not have data from this survey for children under 12, we can see that the next age group, 12-20, appears to be visiting dentists’ offices the most. This is a very good sign and may also be an indicator that children’s dental health before 12 is also very good.

What the chart does show us is that seniors aged 71 and over consult dentists the least, followed by 21-30 year-olds.

No doubt, lower income in retirement age as well as higher costs of dental surgeries for that age group might play a part in keeping seniors out of dental offices.

It is likely as well that the 21-30 age group may not be thinking much about their dental health and/or they have not yet found a job that provides them with dental coverage.

I think it is important to keep in mind that not having visited a dentist isn’t necessarily a sign that someone’s dental health is poor, but it is a sign they have not made a yearly check-up and cleaning a priority.

The key demographics the report narrowed in on were children, for the importance of establishing good oral self-care procedures, and because oral diseases often start in pre-school years. This recommended focus on children was not because there was any evidence, other than in Indigenous and remote communities, that more coverage for children is needed. As we have seen earlier, plans for this exist in all provinces and territories with the exception of Saskatchewan.

Other groups this report focused on were seniors in long-term care, Indigenous peoples, new immigrants with refugee status, people with special needs, and the low-income population. These are groups we might expect would have problems accessing affordable dental care. However, dental care is a provincial and territorial matter voted on by citizens democratically because taxpayers in these areas are the ones who ultimately pay for these services through their taxes.

Some Final Thoughts

Canadians on Twitter are inundated with a barrage of tweets from Jagmeet Singh and the NDP claiming, “Conservatives voted against children.” What he means by this is that the Conservatives do not agree with his “benefit.” The implication is that children are not sufficiently covered, but there is no strong evidence for that. In fact, the children that are most in need of help are those in remote Indigenous communities who have coverage but no access to dentists. This benefit will not change that at all. Meanwhile, the problem Singh is claiming exists, and that his benefit will fix, appears to be already largely covered to varying degrees by most provinces.

The other hard reality is that after children in Indigenous communities, the group most affected by a lack of affordable coverage and access to services is seniors. But I guess saying “Conservatives are voting against seniors” isn’t as sexy as “Conservatives are voting against children.”

There is also the very real possibility that this benefit may hurt those who apply but do not qualify for it, as it could be clawed back like the CERB benefits were, if families apply for the credit and use it for anything other than child dental services or if they fail to keep their receipts.

And what is the real end product here that Canadians are getting and ultimately paying for as a result of this? There may be some relief for those who qualify, but again, to qualify, households must have no existing private coverage, no co-pay for families who make under $70,000, and if you get past these hoops, and your family makes a household income less than $70,000, it will be eligible for cheques of $650 a child annually. The amount drops to $390 if the family income is between $70,000 and $80,000 and to $260 for families with income between $80,000 and $90,000. This federal benefit may cover a small hole for a family that is currently considered low-income, but as I have shown above, children’s dental coverage already exists for low-income families to varying extents across the country. It also starts treating Canadians who make up to $90,000 as low-income. This doesn’t sound quite right, but it does sound like the Liberal and NDP voting blocs. And we must not forget what this benefit has really bought - the support and silence of Jagmeet Singh. That is what Justin Trudeau really paid for with this benefit.

Finally, what originally irked me and set me out on this task to compile all this information was the realization that Canada’s most trusted media outlets had not provided this information to Canadians. We understand that politics is theatre, but why has Canadian journalism failed to critique the plan put forward by Singh and Trudeau? By only discussing what these two have said about the plan, what it will cover, and when it will come out, they have failed to provide Canadians with the information necessary, namely what already exists across Canada in terms of children’s coverage, and what the existing issues are for children’s dental care, to make judgments about whether or not it is the right thing for Canadians, especially at this time when Canada has a debt of 1.1 trillion dollars. An absence of coverage is a silent agreement that this benefit is necessary, and that Conservatives or anyone else who votes against it are “voting against children.” Why does our press seem so uninterested in these things?

If you notice any errors in this article, please feel free to reach out to me at terry.newman79@gmail.com. I appreciate it.