Politics and the English Language in CBC's Investigative Journalism

It's become clear that the words "anti-trans" and "transphobic" have become meaningless ones

George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” explains how language - and therefore meaning - can quickly degrade if an author is writing for political reasons.

Orwell points out two ways this degradation happens: staleness of imagery and lack of precision. He gives three possible explanations for this degradation; the writer may have a meaning in mind that they cannot express for whatever reason, or the writer accidentally says something other than what they mean, or the writer could be indifferent or unconcerned about whether their words mean anything or not.

While all three reasons can be attributed to a lack of skill on the part of the writer, the last appears to be the most critical flaw. After all, if a writer does not care whether or not what they are saying actually means anything in reality, or, worse, they are intentionally obscuring reality by failing to explain a situation fully with concrete imagery or by using a word abstractly, without precision, for political purposes, we must then view this as a purposeful attempt to obscure concrete reality. The result is ugly.

Ugly political writing uses words in a dishonest way as a shorthand to deceive, rather than elaborate, and to signify that some target, some particular person or group of people, is undesirable.

Ugly political writing seems to be everywhere today, but I am going to focus on a recent CBC piece, “Scores of anti-trans candidates running in Ontario school board elections,” to illustrate how political writing is, as Orwell pointed out, abstract, in that it fails to communicate concrete images to further its arguments, and imprecise, in that it relies on the vagueness of terms in an attempt to prove the political point of the author.

Such writing can also go beyond vagueness, extending to ad hominems, the improper use of statistics, non-sequiturs, dishonest and unethical representation of interview subjects, association fallacies, red herrings, and obvious omissions of relevant information. All of these flaws can be found in this piece.

By the end of my article, I hope it will be clear to readers that Jonathan Montpetit, a Senior Investigative Reporter for CBC, was no more interested in fairly and honestly communicating why trustee candidates were concerned about Ontario K-12 school board policies than he was in how these policies might affect Ontario students. His interview correspondence with three candidates suggests Montpetit had decided, before he even reached out to them, the frame and conclusion of his investigation.

I end with a discussion about CBC’s investigative journalism policy, the potential costs to outlets and journalists who attempt to fake a consensus in a society where none exists, and whether or not this piece may have breached “responsible communication,” a very important defamation protection for journalists.

Vagueness, Meaningless Words, & Negative Association Signifiers

Vagueness

Throughout Montpetit’s piece, he uses vague and meaningless language, both in the positive and negative sense. In the negative sense, he claims “scores” of candidates are “anti-trans” and “transphobic” and accuses them of using “transphobic rhetoric.”

What does “anti-trans” mean to Montpetit? He uses this very serious, yet surprisingly vague claim in an extremely casual way. He does not provide a definition, as though the meaning were self-evident, but his definition appears to cast a very broad net, encompassing anyone whose thoughts run differently than the author’s, and seems deliberately designed to quash nuance or questioning. It is, indeed, I would venture, a definition unlikely to be shared by most Canadians.

Is a trustee or parent “anti-trans” if they have no problem with adults transitioning, but have concerns about how transitioning is framed in a classroom for, say, a 9-year-old? Is a trustee “anti-trans” if they encourage children to discover their own gender identity, but at the same time feel uncomfortable with a school board taking steps to affirm that identity, at any age, without parental knowledge? These are examples of the complexity of the issue, but such complexities are erased by Montpetit’s deliberate use of vague language. The label “anti-trans” is incredibly imprecise, and in these particular examples I just provided, I would argue, patently false, but they both would appear to fall under Montpetit’s conception of “anti-trans.” Like “Fascist,” “Socialist,” or “Nazi,” the word “anti-trans” is now used, politically, to describe someone undesirable without having to address that person’s concerns. This is a classic ad hominem. To even further underline how undesirable these trustees are, we are told that “scores” of these candidates were running in the school board elections, the word “scores” not being particularly useful in the mathematical sense, but wielded here to suggest a looming danger, like the scores of Huns who came over the hills to desecrate Rome.

(+) Positive-Sounding Meaningless Words

Montpetit, throughout his article, also uses positive-sounding meaningless words, such as “protections,” “inclusive sex education,” “gender-affirming surgery,” and “gender-inclusive messaging.” None of these terms have any specific content in the article; they are mere signifiers of “things of which we should all approve.”

Protection is, in the proper context, a very clear and specific word. A shield is a protection against swords. The vest my dentist makes me wear before an x-ray is a protection against radiation. Montpetit uses the word “protections” as if it has that same stable and concrete meaning, as if trans students are in danger, and specific policies passed by Ontario school boards are the only shield available to protect those trans students from objective, verifiable harm. But is that true? Are these policies protection in the same sense that a shield is protection? Are raising interest rates protection against inflation? Is solitaire protection against boredom? It depends. It’s complicated. It’s an opinion. Montpetit’s vague use of the word “protections” is an opinion masquerading as a fact, an opinion put forward with the intent to frame certain policies as absolutely essential for the protection of trans students, without having to make an actual argument for any of those policies.

But what are these protections? We, as readers, should have the chance to determine for ourselves 1) whether the policies the authors are referring to do, in fact, protect the transgender community, 2) whether they are the best way to protect the transgender community, and 3) whether they are necessary to protect the transgender community. This is the information parents who elect trustees require. Montpetit, in this investigative piece, provides nothing of the sort and instead uses the vague word “protections” to stand in for all of that. The word subsumes any possibility for debate. They are protections. They protect. Nothing else need be said.

He does this again with “inclusive sex education.” It is left shockingly vague. The term “inclusive sex education” is a value-laden expression, not an objective descriptor. It tells you nothing about the facts of the curriculum, but it tells you everything about how you are supposed to feel about it. Saying someone is against “inclusive sex education” is like saying they’re against “happy things.” It’s a lazy way to beg the question - don’t you like happy things? The words themselves suggest the only appropriate answer, but of course, this is a trick, because what people consider a happy thing is highly subjective. “Gender-affirming surgery” and “gender-inclusive messaging” work the same way. We all believe all human beings deserve dignity, respect, and affirmation, but does that mean we all agree with “gender-affirming surgery” or “inclusive sex education”? I don’t know. It depends. What are the details? Doesn’t Montpetit care about the details? Or is it “anti-trans” even to ask such questions? Why am I more curious about these things than the article is?

Not one concrete image is drawn up to tell us what happens in inclusive sex education classrooms from K-12 in Ontario, who decides that curriculum, or why Canadians shouldn’t ask questions and should accept this curriculum whole-heartedly as good for their children. This seems like a strange choice for a piece of investigative journalism that is supposed to provide information to the public so they can make decisions about which trustee they should be voting for.

(-) Negative-Sounding Associations and Signifiers

Sometimes his word use is not vague so much as marked by negative insinuations. He uses words like “Conservative,” “Christian,” and “Republican” as if the words themselves conjure all the moral depravity he no longer needs to describe. One thing we know for certain by reading this piece - Conservatives are at it again. He strings together negative-sounding signifiers he hopes will communicate that something dark is afoot, words like “conservative lobby groups” and “concerted effort.” It is not even necessarily a fact that all these candidates see themselves as Conservative. But it doesn’t matter that they may not be Conservative. Montpetit wants his readers to think of them as Conservative, since political writing in the CBC has, over the years, created associations between conservatism and moral backwardness, and so in this piece, Montpetit implies associations between these trustees and Conservative groups, allowing the gaps and spaces in his logic to be filled by the imagination, the foggy connecting tissue between Conservatives, Christians, secrecy, concerted efforts, and finally, anti-trans ideology. Montpetit does not aim to persuade his readers that each of these trustees is anti-trans, certainly not with evidence or direct reference to their concerns and why those concerns have no validity, or proper definitions or specifics or anything, but rather lets these vague and dark insinuations do the work. They are linked to Conservatives. They are linked to Christians. There has been a concerted effort. There are lobby groups. They are trying to prevent happy things. They are anti-trans. Whatever that means.

So What Are These Gender-Inclusive Messages, Anyway?

Montpetit had the opportunity in this article to provide Ontario parents with more information, and concrete imagery, to explain what “gender-inclusive messages” means. Instead, he told Canadians the following:

Groups are “seeking to have books with gender-inclusive messages removed from school libraries.”

This sounds terrible. Who would remove gender-inclusive messages from children? The vagueness and lack of specifics here, though, suggest to me that Montpetit distrusted the reader to come to the same conclusions if they were given the missing information. If he trusted his readers, he could have provided two examples of books with “gender-inclusive messages” that were in the news recently, due to a heated discussion recorded during a Waterloo District School Board (WRDSB) meeting in January. All Montpetit had to do was provide a link to this article.

At that meeting, Carolyn Burjoski read from a chapter of “Rick,” by Alex Gina, where Rick “questions his sexuality for not thinking about naked girls, is invited to the school’s rainbow club, and ends up declaring an asexual identity.” Burjoski told trustees, “While reading this book I was thinking ‘maybe Rick doesn’t have sexual feelings yet because he is a child.’ It concerns me that it leaves young boys wondering if there is something wrong with them if they aren’t thinking about naked girls all the time. What message does this send to girls in grades 3 or 4? They are children. Let them grow up in their own time and stop pressuring them to be sexual so soon.”

The other book Burjoski spoke about at that meeting was “The Other Boy,” by MG Hennessy, which discusses the sexual transition of a teen named Shane, who was born female and now identifies as a boy.

Burjoski said about this book, “In fact, some of the books make it seem simple, even cool, to take puberty blockers and opposite sex hormones.” Burjoski called the book misleading because “it does not take into account how Shane may feel later in life about being infertile. This book makes very serious interventions seem like an easy cure for emotional and social distress.”

Nothing Burjoski said intimated that she disbelieves in trans people. Or that she hates them. Or that she wants harm to come to them. Still, the Chair of the meeting, Scott Piatkowski, stopped her from speaking mid-presentation. He warned her not to say “anything that would violate the Human Rights Code.” He said the “Ontario Human Rights Code includes gender identity as a grounds for discrimination and I’m concerned your comments violate that, so I’m ending your presentation.” Within minutes, a vote decided she could no longer speak on the subject. She was accused of discrimination and then silenced. Voicing concerns even just about the age appropriateness of certain subjects was deemed to be violating the Ontario Human Rights Code. Of course, it did nothing of the sort.

These may be the books the allegedly “anti-trans” trustee candidate Terry Rekar referred to as “pornography." I am not surprised that Montpetit left these details out, the content of the hazy term “gender-inclusive messages,” because this is not a piece of investigative journalism. It is a piece of political writing. If he had included the content of, for example, these two books, some of his readers may have accidentally been made to agree with the “anti-trans” candidates. Some still wouldn’t. It’s complicated. It's an open debate. I can imagine many perfectly reasonable parents would. But they aren’t given the opportunity. The books have good messages. They are gender-inclusive messages. These candidates are against inclusivity. They are bad candidates.

For That Matter, What’s the Privacy Policy?

In regards to the privacy policies, Montpetit frames the candidates’ concerns as such: “One common promise is to end the privacy policies that protect trans students from being outed against their wishes.” He goes on to say, “But for trans advocates, such privacy policies are vital for keeping gender and sexual minority students safe.”

But what exactly are these privacy policies that have all these “anti-trans” trustee candidates so concerned? You won’t be surprised, reader, to discover that Montpetit’s vagueness obscures a much more complicated reality.

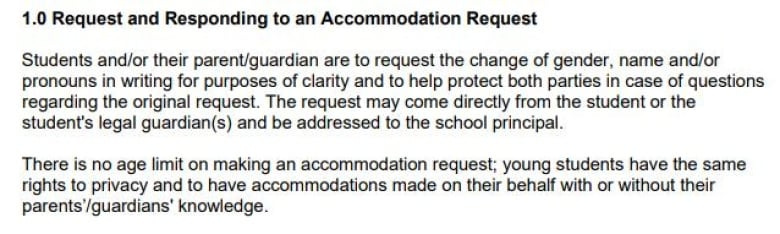

Here is an example of a privacy policy from one of the Ontario school boards (GEDCSB) from a different recent article, “School policy means students can identify by different gender, name without parent knowledge: Some parents oppose policy, while school boards say it protects students,” by Jason Viau, a CBC News Reporter based in Windsor, Ontario (the headline proving that some local CBC Reporters do want to provide clear information, absent of politics, to Canadians):

Having it written down like this in black and white makes it clear that these privacy policies, decided at the school board level, provide privacy for the child from their own parents. We are not talking about adults here. We may not even be talking about adolescents. If a 7-year-old named Sue, after learning about gender diversity in class or at a rainbow meet-up organized by the school, wants to be referred to henceforth as Joe, the school not only must accommodate, but will affirm this new identity, without a medical assessment, and keep this information from Joe’s parents. I withhold judgment on whether this policy is a good idea or not, but to have provided this information would likely have sabotaged Montpetit’s attempts to simplistically tar trustees who question this policy as anti-trans.

Montpetit’s Questionable Use of Statistics

There are two instances in the piece where Montpetit uses statistics erroneously. In the first instance below, he claims that the 2021 Census data provide evidence against trustee candidate Shannon Boschy’s claim that there has been a rise in the number of students identifying as transgender and non-binary. From Montpetit’s article:

“Another candidate, Shannon Boschy, said Ontario's sex-education curriculum was partly to blame for the rise in transgender and non-binary identifying students. In an interview with CBC News, Boschy said this amounted to a "social contagion." (According to Statistics Canada, fewer than one percent of Canadians born between 1997 and 2006 identify as transgender or non-binary.)”

This statistic does not disprove Boschy’s claim. The Census data does not compare the number of transgender-identifying people in Canada now to an earlier time, since earlier Census data on the subject does not exist. This is the first time the Census has ever asked anything about gender identity. The statistics certainly say nothing about whether transgender numbers have risen in Canada since 2014 when these Ontario education policies first appeared. So, Montpetit’s dismissal of Boschy’s claim is completely unwarranted. In fact, Montpetit depicts Boschy’s claim as prima facia absurd, and as evidence for his “anti-trans” position, when I would argue that most mainstream Canadians would simply see Boschy’s claim as a hypothesis requiring research.

One thing the 2021 Census survey data does tell us is that the number of transgender-identifying people is much higher among the two youngest cohorts, 15-24, and from this we might conclude that identifying as a gender minority is, in fact, on the rise among the youngest Canadians. Some major findings of this report include:

One in 300 people in Canada aged 15 and older now identifies as transgender or non-binary.

“Younger generations had larger shares of those who were transgender or non-binary. The proportions of transgender and non-binary people were three to seven times higher for Generation Z (0.79%) and millennials (0.51%) than for Generation X (0.19%), baby boomers (0.15%) and the Interwar and Greatest Generations (0.12%).”

The Census survey report gives three possible reasons that many more younger people are identifying as a gender minority. First, it suggests that social and legislative recognition of transgender, non-binary, and LGTBQ2+ people may play a part. Second, it suggests that younger generations may be more comfortable reporting their gender identity than previous older generations.

Third, the report says, “Generation Z was born in the Internet age, and millennials came of age during a time when the Internet was changing the way we gather and process information. The Internet, along with social media and web-connected personal devices, may have contributed to the increasing awareness of gender diversity—especially among younger generations—by providing transgender and non-binary individuals with virtual support communities and answers to questions that were less accessible to older generations.”

It may be one of these three causes. But there is obviously a fourth possibility, one suggested by common sense but rejected by a certain strand of contemporary political ideology and, perhaps for that reason, left out of the report’s conclusions. Maybe Montpetit does not like the term “social contagion” because of its negative connotation, and fair enough, but put the term aside, and look at what Boschy’s claim, essentially this fourth possibility, actually communicates. It puts forth the proposition that greater awareness campaigns in schools might convince some confused children and adolescents, seeking an identity, seeking an explanation for their anxiety, for their sadness, for their discomfort in their changing bodies, that they are trans when they may in fact not be. The claim is not on its surface insane at all. Children and adolescents try on all sorts of identities, some more long-lasting than others. Anyway, Boschy’s claim may not be true. But it could be. Or at least a factor. Who knows? I won’t pretend to have a definitive answer on this matter. More research needs to be done. But Montpetit shouldn’t pretend to have one either. Montpetit is certain this never happens? He is so certain that anyone who even suggests the possibility is anti-trans? This is not journalism. This is politics.

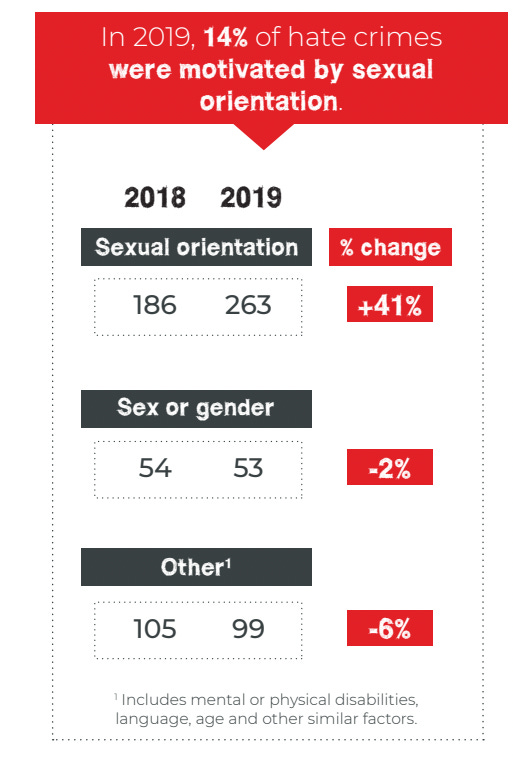

In Montpetit’s second use of statistics, he uses them to provide evidence that hate crimes against transgender people are on the rise. From his article:

“The data that we have in Canada shows that hate crimes against our communities are continuing to rise," said Lyra Evans, a school board trustee in Ottawa who is transgender.”

However, if one actually clicks on the link and reads the report, they will find the opposite is true, according to the official definitions on page 15.

In his use of these statistics, Montpetit appears to have read the wrong number. Police-reported hate crimes are broken up into two categories, “hate crimes that are motivated by hatred of a sexual orientation” and “hate crimes motivated by hatred of a gender expression or identity.”

According to the report, “sexual orientation refers to a person’s physical, romantic, emotional or sexual attraction.” This category does not include crimes motivated by hatred targeting the transgender population, as those are collected under the category of sex or gender identity. Police-reported hate crimes motivated by hatred of a gender expression or identity, however, and this includes transgender, are the smallest in number, and while the majority of the 55 attacks occurred within the last three years of the nine-year period from 2010-2019, attacks have actually decreased, not increased, over those last three years (15 incidents in 2017, 13 in 2018 and 11 in 2019).

Let us not quibble, though, and assume good faith on the part of Montpetit. Even though these crimes have gone down in the last three years, they were going up before that. By mentioning this statistic, Montpetit implies that specific policies that these particular trustees are questioning are necessary to stave off hate crimes against transgender communities. But this is a non-sequitur. What does the number of hate crimes have to do with education policies? Have these policies been proven to reduce hate crimes against transgender people outside of schools? Where is the study? To suggest that these candidates should not have problems with any of these school policies because hate crimes against transgender people may rise suggests that any questioning of these policies or of any “sex inclusive” curriculum is detrimental to transgender safety, nay, will even cause hate crimes to happen. This implication is unproven. This is a dirty trick, especially for an investigative journalist, because it shuts down any conversation about the policies in question. They become something sacred, like the holy trinity. No topic should be sacred to an investigative journalist.

The Research Process: What You Omit Can Reveal Major Ethical Flaws

The following omissions center around Montpetit’s investigative process in regard to what interview information he chose to use and what he chose to omit. I teach research methods, so I can easily spot instances where someone sets out to prove their desired narrative in an investigation, regardless of what facts they come across or ethical standards they might breach in dealing with their interview subjects. In academia, there are penalties if researchers are found to have purposely broken ethics by misrepresenting interview subjects or their data in their publications. These penalties may include article retraction, losing research funding, and reputational damage, to name just a few.

A few trustee candidates have allowed me to publish Montpetit’s communications with them. I believe they show that Montpetit was uninterested in presenting any of these candidates’ views in a fair or honest way.

You can review the communications between Jonathan Montpetit and the following candidates: Peter Wallace, Chanel Pfahl, and Shannon Boschy. Note what did and did not make it into Montpetit’s piece or his television interview.

In the emails, Montpetit plays polite with these candidates, but it is clear from his line of questioning that he is aiming to find a smoking gun, some link between PAFE, FAIR, Christians that Care, and Blueprint for Canada that will damn them all, and is not genuinely interested in candidates’ concerns. It’s a fishing expedition. And what he’s fishing for is a giant red herring. It wouldn’t matter what associations any of these people had. These candidates could literally have met up with Voldemort and received training in the dark arts and that would still have no bearing on whether their concerns about books or policies were valid.

Chanel Pfahl

Here is how Montpetit chose to frame Chanel Pfahl in the piece after his communications with her:

“One candidate, Chanel Pfahl, a former school teacher, faced criticism recently when she published on social media the confidential details of online support group meetings for visible minority and LGBTQ students…”

I asked Chanel about this. She said she shared it because she thought it was important for the public to know, as per the memo above, that the Rainbow Group was including children from as young as kindergarten in their talks.

By sharing an image of the document, the google meet code was shared, but this alone would not have provided access to the meeting itself. Therefore, the confidentiality of the students was never breached or in danger. To access the meetings, one would still have to log in from an OCDSB account.

Montpetit chose to use one of Chanel’s tweets in his article, rather than her interview responses, which would have been fine, if he hadn’t completely decontextualized her words.

"I'm actually trying to protect kids from a toxic ideology," Pfahl said in a tweet explaining her actions. "Can't say the same for whoever is trying to have secret meet-ups with lesbian kindergarteners."

In context, we see that Chanel was responding to the document above and the idea that someone in kindergarten should be meeting with a Rainbow Club to discuss their sexuality. To Montpetit, this is evidence she is “anti-trans,” rather than, perhaps, anti-my-kids’-school-discussing-sexuality-with-my-kindergartener. I doubt Montpetit’s labelling of Chanel as “anti-trans” would convince most Canadian parents if they had been provided with this context.

Shannon Boschy

Shannon Boschy was asked by Montpetit if he would do an on-camera interview, and he did. Shannon was worried that Montpetit might try to frame him in a specific way, so he set up his own camera next to Montpetit’s during the interview.

Montpetit never used the on-camera interview with Shannon. Shannon also provided Montpetit with several references to back up the reasons for his concerns about the privacy policy in his email correspondence with Montpetit. These references, along with Boschy’s statement in the email, “We need to have open and honest public debate to ensure we are providing the best possible support for kids with Gender Dysphoria and who are Gender Non-Conforming,” never made it into Montpetit’s “anti-trans trustee” piece either.

Instead, Montpetit framed Shannon’s concerns like this:

“His opposition is based, in part, on how his own child transitioned genders. Boschy said the school didn't inform him and that contributed to a rift with his child. ‘I lost my relationship with my child.’”

Montpetit follows this heartbreaking revelation from Shannon by dropping it and then dismissing Shannon’s feelings and experience entirely by announcing, essentially, that trans advocates know best. This is, by far, the darkest and most inhuman part of Montpetit’s coverage.

The Copy of the Omitted CBC Video Interview with Montpetit & Boschy

Montpetit also insinuates that calling gender dysphoria a disorder makes Shannon “anti-trans.” But it is a disorder, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR)1 or DSM-5-TR. ADHD is also a disorder. So is autism. So is depression. There is no insult implied by calling a disorder a disorder.

Other candidates mentioned in the piece were labelled “anti-trans” or accused of “transphobic rhetoric” for making statements I cannot verify in contexts I do not know because Montpetit has not provided a link, image, or full quotation. Yet these alleged comments are peppered throughout his piece as evidence of “anti-trans” candidates.

In all of Montpetit’s communications with these candidates, it would not have mattered one whit what they said. Montpetit had already decided what his frame was going to be, and he was going to have that frame, fairness and diligence be damned. Omitting evidence that does not suit your narrative is bad and unethical journalism, but it is also clearly a hallmark of ugly political writing.

Glaring Omissions: The Cass Review & The Existence of Detransitioners

The final glaring omission from this article is the complete lack of important information voting parents might need to know about affirmative policies, information both Boschy and Wallace pointed out to Montpetit in their email correspondence, information about Tavistock, the Cass Review, and the existence of de-transitioners. This is not to say this information proves the candidates right. It just suggests they are not some radical, fringe coalition of transphobes, but instead just genuinely concerned citizens and parents who have some of the same concerns as many people and governments in Europe.

Peter Wallace from Blueprint for Canada also gave Montpetit this information through email correspondence:

“It is worth noting that many countries in Europe are now backing away from gender-affirming medical care for minors. (Notably in the UK, France, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway.) In my view, Canada simply hasn’t caught up yet. As you may be aware, the Tavistock clinic in the UK has recently been forced to shut down and is now the target of a class action lawsuit with over 1000 claimants. These claims are from adults harmed by gender-affirming care policies which were performed on them when they were younger and driven by ideological motivation rather than science-based treatment. A similar story now appears to be unfolding with the group “Mermaids” also in the UK. You can confirm all this with google searches if you wish.”

Apparently, Montpetit did not wish.

This editorial by The Guardian gives a breakdown of what led to the Cass Report. Like the privacy policies at some Ontario school boards that automatically affirm a child’s chosen identity, before it was shut down, the NHS’s specialist Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) was taking “a child’s expressed gender identity as the starting point for treatment.” By starting with the affirmative approach, other possible explanations for dysphoria may be ignored, which in many cases at NHS led to a misdiagnosis of transgender, which was then followed by any number of inappropriate treatments including puberty blockers, cross-sex hormone treatments, and irreversible surgeries. These quick affirmations followed by inappropriate treatments led to some children and adolescents later regretting their transitions and becoming detransitioners, like Keira Bell, who believes she should have been challenged on her decision to transition. This led to court cases against the clinic, which led to an independent review of the clinic and the quality of services it was providing.

The Cass Review is an “independent review of gender identity services for children and young people” led by Dr. Hilary Cass, a former president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. It can be read here.

Here are some major findings:

From the point of entry to GIDS, there appears to be predominantly an affirmative, non-exploratory approach, often driven by child and parent expectations and the extent of social transition that has developed due to the delay in service provision.

From the documentation provided to the MPRG, there does not appear to be a standardized approach to assessment or progression through the process, which leads to potential gaps in necessary evidence and a lack of clarity.

There is limited evidence of mental health or neurodevelopmental assessments being routinely documented, or of a discipline of formal diagnostic or psychological formulation.

The Review is not able to provide definitive advice on the use of puberty blockers and feminising/masculinising hormones at this stage, due to gaps in the evidence base; however, recommendations will be developed as our research programme progresses.

Dr. Hilary Cass points out that “this is an area in which [there are] incredibly strongly held views and the debate can get very toxic because of that. People are actually afraid to talk openly and we have to find a way to allow them to do so in a safe environment. Ultimately, we’ve got to find a way to put the animosity aside to come to a shared consensus and to find the best possible way forward for children and young people and their families.” This echoes Shannon Boschy’s statements, which were labelled “anti-trans” by Montpetit. Yet, Montpetit’s article does quote Fae Jonstone, a trans advocate, in saying “Transgender students are best placed to determine how and when they come out.” Why ask a trans advocate alone? Why not also ask a child psychologist or medical experts in that field? Why not ask those who have de-transitioned? Why not reveal the truth of the complexity of the issue? Because those answers would interfere with his narrative.

Failure to Report Accurate Numbers on Election Results That Hurt His Narrative

Montpetit’s last update on these “scores” of “anti-trans” candidates on October 25th announced that “anti-trans” candidates failed to make major gains in Ontario school board elections, according to unofficial results at the time. New information has since come in, and it appears now that 21, not 10, as Montpetit had asserted, of these “anti-trans” trustees were elected. There has been no update to Montpetit’s piece. The new number would, of course, be damaging to his narrative, though, as it would suggest that thousands of Ontario parents are sympathetic to the concerns of these trustees. Montpetit was at great pains to depict all these trustees as a radical fringe trying to infiltrate the mainstream, but it seems that a large chunk of the mainstream, far more than Montpetit implied, like these candidates just fine. Perhaps Montpetit has failed to update his article because he is unready or unwilling to confront the fact that these trustees’ concerns are shared more widely by the public at large than he would like to think. Perhaps even he is uncomfortable with the insinuation that thousands of Ontarians would also, by extension, be defined by his article as “anti-trans.”

I reached out to Jonathan Montpetit, CBC’s Senior Investigative Reporter, to ask him a few questions about his investigative process for this article.

His final answer:

Hi Terry,

Thanks again for reaching out to us and for your interest in continuing the conversation around these important issues. Our reporting was conducted in line with CBC’s Journalistic Standards and Practices (which you can consult here). We think the story stands by itself.

Best, -Jonathan

CBC Standards for Investigative Journalism

And here I get to my major issue with all this. Montpetit’s article is labelled “investigative journalism.” This might seem strange to readers. The term “investigative” evokes images of hard reporting, the discovery of heretofore hidden facts and documents. An investigative journalist is like an archaeologist that uncovers the deepest hidden realities of the world. But that’s not what this piece is at all. It’s an opinion piece. More to the point, it’s a piece of political activism. It could have been written by one of the trans advocates themselves. Not that there is anything wrong with that, in theory. All newspapers have opinion pieces. They are a historic and valid art form essential to the free press of a democratic society. A well-written opinion piece in a widely distributed newspaper could be a powerful agent of societal change. But then why is this piece called investigative journalism? Then I did as Montpetit suggested, and checked the small print, CBC’s Journalistic Standards and Practices. Here is CBC’s own definition of investigative journalism:

“Investigative journalism is a specific genre of reporting which can lead to conclusions and, in some cases, strong editorial judgments. A journalistic investigation is usually based on a premise but we do not broadcast an investigative report until we have ensured that the facts and evidence support the conclusions and judgments.

To achieve fairness, we diligently attempt to present the point of view of the person or institution being investigated.”

Ah, so they covered their ass. CBC has decided that their opinion pieces can be called “investigative journalism.” No fear of litigation there. Except for maybe that last bit about fairness and diligence.

This is an opinion piece. It is a bad and unethical one, for all the reasons I have pointed out. But the biggest problem is that it’s not even labelled an opinion piece. It pretends to be a piece of investigative journalism, and so its opinions are hidden, invisible, disguised as facts. He can call people names, make the most horrible insinuations, jump to the wildest conclusions, make the most unverifiable of assumptions, ignore facts that disrupt his narrative, and frame it all as a piece of news. People expect opinion pieces to be subjective and flawed. But when they read news, especially “investigative” news, they expect well-researched and documented conclusions. So that’s what they’ll see. Most people who read this piece won’t even see that it has opinions. Everything sounds so clear and true and indisputable. Until you read it carefully. It cloaks itself in the prestige of a highly respected genre of reporting so it can sneak through a subjective and political argument just as opinionated as anything you can find on an editorial page. It’s insidious. And it’s deliberate.

Attempts like this one, to fake a consensus until you make a consensus, are one of the reasons why people no longer trust journalism and journalists. There is a particular brand of ugly political writing in Canadian media that pretends there is a national consensus (an assumed consensus) on an issue when there is not. In these pieces, the world is simple, everything has already been decided, and journalists frame as facts things that are not only mere opinions but are actually opinions held by a kind of fringe minority themselves of academics and journalists. They are the ones with the idiosyncratic views, and yet they speak as if 100% of people agree with them all the time. It is as if they are trying to make that consensus come into existence through the sheer force of believing and putting forward that it exists.

Montpetit refuses to define “anti-trans” throughout the entire article or to pin himself down on the number of “anti-trans” candidates. Sometimes there are scores, other times there are dozens. In a later article, he claims a CBC investigation had identified “more than 50 candidates.” The “more than 50 candidates” has a hyperlink that any reasonable person would assume, when clicked, would provide evidence of 50 such candidates, but alas, the hyperlink only leads back to the piece I am critiquing now. But anyone who did not take the time to inspect it might erroneously assume CBC did provide such evidence. They might erroneously assume this was a piece of good old-fashioned reporting.

This investigative report claims that these individual candidates’ choices to run are part of a “concerted effort by conservative lobby groups,” strongly implying their platform is the product of some shadowy kabal of networked evildoers and not their own personal, legitimate concerns. And when candidates detail their personal concerns through email or on-camera, Montpetit throws those concerns in the wastebasket. The irony of Montpetit calling these candidates “conspiracy-minded” when he himself was looking for nefarious connections everywhere should not be lost on readers. Association fallacies are one of the most commonly found in ugly political journalism today.

I think it is clear that Montpetit had a narrative that he wanted to spin. He did not care about whether there was any legitimacy to the candidates’ concerns. He did not care that this would unfairly prejudice voters against them. He did not care about their reputations or the threats they and their families might receive as a result of being called “anti-trans.” He did not care about Ontario parents or their children. He only cared about who these candidates were in contact with and what trans advocates had to say.

But it is important that words have meaning, and that vague and incendiary labels are not thrown around as a way to silence people we disagree with. Serious accusations require serious consideration because they have serious effects.

Responsible Communication or Defamation?

Laws exist to protect the freedom of expression of journalists and for good reason. There are instances in which journalists will uncover well-researched and indisputable information that society should know about that damages an individual’s reputation.

However, journalists can also breach the limits of what is considered “responsible communication” in their reporting on individuals. Defamation charges can be brought against a journalist if what has been written defames someone erroneously, crosses the limits of “responsible communication,” and causes provable reputational harm.

If he were brought to a defamation case, Montpetit would be asked if there is sufficient evidence to justify his use of “anti-trans,” “transphobic rhetoric,” and “transphobic,” as well as the nefarious-sounding patchwork of associations he attempted to wrap all of these candidates in. If found not to be justified, the court would also look at whether or not harm can be proven.

By presenting these candidates as “anti-trans,” among other things, I believe that Montpetit may have opened himself up to this. Montpetit never proved any of these candidates were “anti-trans” or “transphobic” or guilty of “transphobic rhetoric” against trans people. Being concerned with the effect of school board policies on children is not the same thing as having a fear or hatred towards transgender individuals. I would advise all of these candidates to seek a lawyer and review recent defamation cases here.

CBC’s Ombudsman Jack Nagler fields complaints and concerns about CBC’s reporting. If you too feel that Jonathan Montpetit’s or any other reporter’s coverage is troubling in some way, you can file a complaint here. Maybe you’re an Ontario parent who feels misled by Montpetit’s coverage.

If you feel there are any errors or corrections that need to be made in my reporting, please contact me at terry.newman79@gmail.com.

Hear, hear. My favourite part: "Attempts like this one, to fake a consensus until you make a consensus, are one of the reasons why people no longer trust journalism and journalists. There is a particular brand of ugly political writing in Canadian media that pretends there is a national consensus on an issue when there is not. In these pieces, the world is simple, everything has already been decided, and journalists frame as facts things that are not only mere opinions but are actually opinions held by a kind of fringe minority themselves of academics and journalists." We all need to keep calling out this tactic clearly, methodically, and in the level-headed manner exemplified by this excellent piece.

Unfortunately, we now live in a world of milliseconds attention spans, and most readers only scan through headlines. A conclusion is reached at that time, and "journalists" often will just fill their piece with enough words to get paid, knowing that almost no one will take the time to read the piece, especially if fits in their own confirmation bias.

Social media is hell for this behavior. Even such a terrible site as Twitter took steps not so long ago to detect when people shared articles without even opening the underlying link and ask people if they really want to share it without reading it.

So unsurprisingly for the article you cover, most people will have scanned it at best, and just nodded in agreement.